An Overview of the Open Source Ecosystem

Published on

In nearly every role I've held there have been people that do not understand open source. That's not to say that they couldn't, they've just never had to truly understand the nuances of the ecosystem, the players involved, their motivations, or the criticality of the delicate balance being held. I often become "the open source guy": that person in your organization that gets it. The one others refer you to when you have a question about open source software.

In this (unapologetically long) article, I attempt to provide an overview of the open source ecosystem for the uninitiated. It will not cover 100% of the use cases, intricacies, or issues, but hopefully it will be sufficient to send to your colleagues that need the overview so that you can then go one level deeper to discuss whatever issue you are currently facing.

To make it more approachable, I've broken this article up into two sections: Producers and Consumers. There's an introduction below as well, and at the end I discuss a few strategies I think would help us support the ecosystem to ensure this critical set of software remains secure and is available to all of us for a long time.

Jump to "Producers and the Supply Chain"

Jump to "Open Source Consumers"

Jump to "A Call to Action"

What is Open Source?

Generally speaking, any software for which the copyright holder has publicly shared the code - and attached a license releasing some of their copyright - could be considered open source software. However, the commonly accepted pattern (and thus definition) is a piece of software whose code is continuously published on an open platform (i.e. GitHub, GitLab, etc.) and typically where issues (bug reports, feature requests, etc.) are publicly posted and discussed. In most cases, a public contribution model is also adopted, but this is not required for a piece of software to be considered "open source".

And at its core, the Open Source Software (OSS) ecosystem is a distributed and fractured producer-consumer market with non-traditional economics and incentives. Producers and consumers come together through various distribution channels and interaction points to create final software systems that solve real world problems.

Note that OSS and FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) are not the same. The fundamental difference is that FOSS is, of course, "Free". In common parlance, however, this is what we mean when we say "open source". However, technically it does not have to be "free" to be open source.

There is a good explanation of the various aspects of what makes something "Open Source" on opensource.org, the homepage for the Open Source Initiative (OSI). This is a good overall resource for open source definitions and information.

In general, there are four "freedoms" that are required for something to be open source:

- Use: Anyone must be able to use the software for any purpose and without having to ask for permission. The license cannot restrict access to certain groups!

- Modify: A consumer of the software must be able to modify it for any purpose. However, there can be restrictions on whether or how those modifications are distributed (see "Share" below).

- Share: A consumer of the the software must be able to share it with others for their use with or without modifications. In other words, if I build a piece of software on top of another piece of software, I must be able to distribute my own software (with the underlying open source piece). That said, there can be restrictions on how I do so, for example, I might need to attach a similar open source license to my software, or might not be able to do so for commercial purposes.

- Study: Anyone must be able to study how the software works and inspect its components. Among other things, this means that a free release of a software binary (without the underlying source) would not count as "open source" because the source code cannot be inspected.

Value of Open Source

This article is going to point out a number of flaws in the open source ecosystem. I believe it is important to not hide these topics, but I also am a staunch believer in the value of open source software - not just the monetary value, but the value to society. That said, some very smart people have actually looked at the financial value of open source software, and so I wanted to call that out before you, dear reader, finish this article and believe me to be a nay-sayer.

In their paper titled "The Value of Open Source Software" from January 2024, Frank Nagle, Manuel Hoffman, and Yanuo Zhou of Harvard Business School highlight that if the world were to rebuild all of the open source software themselves, the cost would be around $8.8 Trillion US dollars. You can read the paper yourself (linked above), but the key here is that rebuilding all of this from scratch would take an immense amount of time.

Even this extremely high value is exceptionally low, as is noted by the authors, because it does not include the (re)development of open source operating systems such as Linux. Considering Linux runs the vast majority of Internet servers, the cost to rewrite it (many times over for each company) would be immense.

Examples of Open Source Software

As you can imagine, there are many different types of open source software. Generally speaking, there are four big buckets:

- Reusable modules for building other software

- Low-level system software

- Complete software installed "off the shelf" by users and organizations

- Non-end-consumer systems

Reusable Modules

This category is by far the largest in the ecosystem in terms of number of projects. These modules includes both large and small code repositories, single contributors up to large corporate support, and code that is both widely used and barely ever accessed. Note that these are almost always not usable by themselves, they are only used to compose larger systems.

Reusable modules can pose a high risk to overall security of a software system's digital supply chain due to the complexity of dependency chains, distributed and unvetted contributor profiles, and extremely broad use across all other end-consumer software. That's not to say that a system can't be secure when using reusable open source modules, it simply means that consumers need to be conscientious when doing so.

Examples:

- The "V8" JavaScript engine

- Used within the Google Chrome browser, but also the basis for Node.js

- Supported by Google, but with numerous individual contributors from the community

- Strong contribution guidelines and security procedures

- Limited use directly by applications given its purpose

- The Flask Python API framework

- Used by many thousands, if not millions, of websites (26+ million weekly downloads)

- Entirely supported by the developer community (no specific corporate sponsor)

- Strong contribution guidelines, but no information on security protocols or scanning

- The left-pad JavaScript module

- 47 total lines of code with 9 contributors total (but really only 1 primary)

- Has been deprecated, but still downloaded 2.6 million times a week

- A JavaScript internationalization tool called jquery-localize

- 8 individual contributors, but really just 1 person maintaining it

- Basic contributing guidelines, but no security or other processes in place

- About 600 weekly downloads

Low-level System Software

This category is a bit of a hybrid between a reusable module and an end-user system. A low-level piece of software in this category is used to build other software systems, but not typically as a "module" like the category above. Instead, this software represents more foundational pieces of functionality to software systems and often sits in front of, or underneath other complete systems.

Low-level software like these pose some of the highest risk to the overall security of the ecosystem due to the fact that so many final systems ultimately rely on the (relatively small) set of software in this category.

Examples:

- The openSSL encryption toolkit

- Used in nearly all open source operating systems as the basis for secure digital communication

- Solely supported by community contributions with strong security and contribution guidelines

- Given that over 90% of the world's Internet servers run Linux, and by default openSSL is the software used to provide secure Internet connections on them, you can imagine the broad reach of a vulnerability in that software.

- The nginx web server

- Used by over 1/3 of all websites as the "front door" for web traffic

- Open source project with many community contributions, but with a for-profit company behind it

End-User Complete Software

These are typically large systems that can be installed and operated by users and organizations. They span the IT ecosystem from word processors to image manipulation to operating systems, but importantly are not typically the building blocks for other systems (perhaps excluding the open source operating systems like Linux).

These systems are susceptible to open source supply chain attacks, but they are typically maintained by organizations, companies, or foundations with decent resources to protect them. Sometimes these systems fall into the category of "open source", but not free - or more often, free to install, but with paid premium support and features that really are necessary for any substantial installation and use.

Examples:

- LibreOffice, an open source office suite

- Desktop suite of applications supporting word processing, spreadsheets, etc.

- Strong non-profit organizational development team with many community contributors

- The Moodle learning management system

- Web application codebase that anyone can install, configure, and use, but with commercial support

- Many community contributors, but with support of a commercial entity

- Strong contribution process with testing and (some) defined security processes and practices

- The Ubuntu Linux distribution

- A full operating system (OS) for laptops, desktops, and servers

- Many contributors across the world, but with a formal (non-profit) organization behind it

- Available premium commercial support

- Extremely strong contributing guidelines and security processes

Non-end-consumer Systems

These are typically full systems that are specific to their producers and maintaining organizations. They are generally open source for transparency only, and while they may accept contributions, they are generally not used by anyone else in their current state.

Examples:

- The Mozilla Foundation's website

- Accepts community contributions, but mostly internally maintained

- Is not a dependency of any other project, and is not intended to be used by anyone else

- The cyber.dhs.gov website

- Hosted by the Department of Homeland Security (CISA, specifically), not a dependency of any other system

- Some community contributions accepted

Producers and the Supply Chain

When we talk about "producers" in the open source community we typically mean individuals and organizations that create and maintain specific pieces of code. Importantly, they are almost always consumers of open source as well: their code uses other OSS modules as dependencies. Typically, a producer will also use their own OSS modules in final software systems like full web or mobile applications or embedded system code.

There are lots of questions inherent in this "producer" role: why do they do it? How do they keep up with the pace of development? How do they market their product? Who has the ability do this? Where is the code stored and how is it accessed? I won't be able to fully answer all of these, but we'll at least tackle some of them.

Terminology Note: an "upstream" project is one that is consumed by another system which consider to be "downstream". You'll see a diagram of this later.

Producer Roles

Contributor: Anyone who provides input into the project. That can be bug reports, documentation, security reports, code, etc.

Committer: A subset of contributors, typically understood to be someone who contributes code specifically.

Maintainer (or sometimes "Admin"): A subset of committers, a person in charge of maintenance of a code repository, often including reviewing and approving contributions from other people, changing minor settings or workflows, and participation in the development of project processes and policies.

Owner: A subset of maintainers, one or more people who have 100% full rights and access to the code repository. These are the only people that could take seriously grave actions on a repository (like deletion, renaming, or other critical settings). Typically access control (that is, who is allowed to become a committer or maintainer) is also the responsibility of owners.

Producer Motivations

It is nearly impossible to know why anyone does anything, but below are some of the common sentiments around the reason open source software exists and why people continue to create and maintain it.

Need

Most contributors to open source software have a need for the code they contribute. In other words, if there is a useful code library out there that solves 95% of your problem and you believe that you can write code to solve the last 5%, then it is more efficient for you to use that open source code as a base to create on top of. If you do that, it's not too much more effort to contribute that code back to the upstream source code repository.

The "need" argument doesn't really answer why someone would open source their code in the first place, of course.

Altruism

Many people in the open source community consider themselves to be altruistic: that is, they create and share code for the betterment of all developers and the software they create. This may seem foreign to many, but it is a very common sentiment among OSS contributors.

Notoriety

Somewhat in contrast to the altruism reasoning is notoriety. There are some OSS contributors that want the attention. They strive to create something popular that will get them conference speaking engagements, clout among their peers, or even prestigious jobs. This is not to say that these people aren't also creating things out of need - the two reasons can coexist.

Money?

To be blunt, most people that support open source software do so without the expectation of making money with that particular work. The money simply isn't there for most projects and contributors. Of course, that experience can propel some developers into good jobs, and there are a number of companies that do in fact make money - and pay developers on staff - supporting open source projects. Organizations like the Linux Foundation, open source companies like RedHat, and big tech companies like Google all do this; however, those opportunities are few.

If we're talking about initial motivations for a producer to open source a project, it simply isn't a financial decision. This is relevant because incentivizing open source contributors to continue their support often cannot be purely financial. That's not to say that contributors couldn't be motivated by money in the future, but the understanding is that one should not expect to be paid for OSS contributions.

The role of Software "Foundations"

The vast majority of open source projects are owned (in terms of copyright), run, and managed by individuals. A number of open source projects are run by corporate entities (Facebook's React library, RedHat's Enterprise Linux distribution, Mozilla's Firefox web browser), typically growing out of the organization's need for the functionality and desire to engage with the wider developer community. A third category exists that is a hybrid of sorts: software foundations.

One of the oldest foundations is the Apache Software Foundation (ASF). This (as with most foundations) is a non-profit (501(c)3) and does not take ownership of the projects under it, but rather provides them with some amount of resources and legal protection.

For example, a project under the auspices of the ASF can get hardware, communication tools, and business infrastructure provided for them (under certain conditions). Because ASF is an independent legal entity, it can provide some shelter from legal suits directed at a project (and its maintainers) under the protection of the foundation. In addition, foundations can offer companies and individuals an entity to donate resources to and be assured that those resources will be used for the public benefit.

In nearly most cases, projects under a foundation like ASF do not need to follow terribly strict development, testing, security, or licensing guidelines. This differs from one foundation to another, but in general this means that while the collaboration and resourcing may be regulated by the foundation, the quality of code is not necessarily so.

Maintenance Models

There is no single model for long-term maintenance of an open source code library. Popular open source projects will typically have a document called "CONTRIBUTING" (or similar) within the code repository which outlines how an individual can (and should) contribute code. These documents tend to outline things like code style guides, testing practices, build processes, documentation requirements, and more. Of course, not all projects are created equally, and in many cases - even for popular repositories - these requirements and processes can be invisible to people not in the core team.

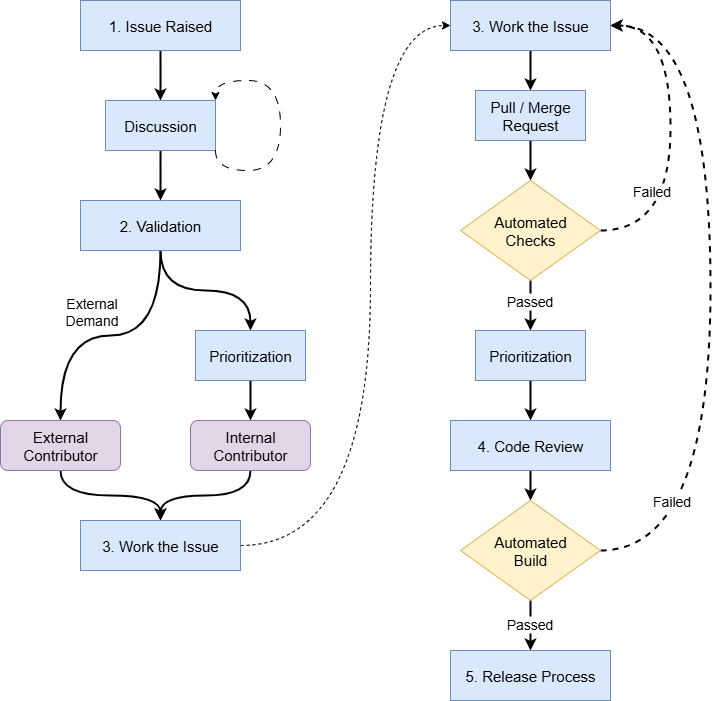

That said, there is a general pattern that you see repeated regularly, which is outlined below. The reader should be warned, however, that this is by no means a "standard" or even necessarily the best approach. Many projects have different requirements that demand different processes.

1. Issue Raised

An issue is raised on one of the project's communication channels. This could be in an issue-tracker tool only accessible to the core team, an email distribution list, or even someone ranting on social media. Often it is a public-facing (i.e. open source) issue tracker such as the "Issues" on a GitHub.com repository. These issues could be bug reports, feature requests, security reports, or even just questions about the workings of the codebase under certain conditions.

Generally speaking, anyone can raise an issue about the code library in this manner. This is important, because it means that open source maintainers can sometimes be inundated with requests, sometimes for valid concerns, and other times as an intentional, dedicated campaign for radical change. But remember: these maintainers may be unpaid volunteers who do not think of themselves as your vendor, highly business-centered corporate employees who do not think of you as their customers, or anything in between. The initial response to the issue may very much depend on who reported it and how, coupled with who received the report and how it meshes with their motivations.

2. Validation

There may very well be discussion in the issue's comment thread about validity, nuances, potential resolutions, etc. Importantly, the "validity" of an issue is very subjective to the maintainer's motivations. Ultimately a decision might be made to close the issue for various reasons (for example, it might be a duplicate of another issue). Feature requests will typically have discussion about whether the library is suited for that feature or if it should belong elsewhere (in another code library, perhaps). Typically you will see some early prioritization of issues here as well.

For bug reports, the conversation usually centers around more traditional "validity" - that is, does the bug really exist, or was the issue due to some other factor, possibly user error. In most cases, unless the bug can be replicated by someone (with well documented steps), the bug will be closed or deprioritized.

3. Work the Issue

Once an issue has been validated, anyone can work on it - not just core team members (those with direct commit access), but anyone in the world. The path will likely be different depending on whether the incoming code change originated within the core team versus an external party.

If the core team intends to work the issue, it will need to be prioritized. This process might happen in private, but sometimes an open source repository will mark issues with their priority level or a target milestone for completion. More established, structured teams may have a full Software Development LifeCycle (SDLC) process with typical agile development activities.

Regardless of the internal process, if there is significant external interest, an outside contributor or organization may do the work themselves. This might happen even if the issue is prioritized by the core team.

4. Code Review

In mature codebases there will be many automated and manual checks before code gets merged back into the upstream source repository's trunk. These checks may differ a bit depending on the origin of the code contribution, but generally they will be similar regardless of who created the change - that is, whether it's an internal contribution or an external one. The final check is typically a manual, human review of the contribution performed by a core team member.

The first line of defense for code quality will be any pre-built unit and integration tests that a developer can run on their own before even submitting a request to merge the code. Additionally, there may be some code style guides, code quality tools, and other automated processes in the repository's Continuous Integration (CI) automation.

Once a request to merge is submitted, automated checks will run the tests, code quality scans, and any other automated processes (such as security scans, if they exist). A failure here means the developer (internal or external) has more work to do, and it prevents unnecessary human time spent on reviewing the code.

If the request is from an external contributor, the core team will need to prioritize the review in their own schedule. This can cause delays, but is necessary to protect the codebase. This last point should not be dismissed quickly. The amount of time to properly review a contribution is significant, and again, these maintainers are often unpaid volunteers, which means they must prioritize this work in addition to everything else going on in their lives. A good review involves not just checking automated test output, but reading every line of the code submitted, associated tests and coverage, documentation and other non-technical artifacts, and comparing against architectural decisions and style guides.

A common fault of novice contributors is assuming the review of their contribution is easy, but it often is not, especially if the contributor did not put extra effort into crafting a well documented changeset.

5. Release Process

This is the last step in the process and varies widely. There is such discrepancy in release processes that it doesn't even make sense to try and elaborate on them here. The only real consistent piece is that the final, fully built code is available for public download on some platform.

For environments like Node.js, Python, and Java this might mean publishing the distributable code package to a package manager service like npm, PyPi, or Maven (respectively).

In all cases the version number of the distributed package should be updated. Sadly, this does not always happen, but for this example maintenance model we will assume that it does.

While not all projects use it, the "Semantic Versioning" (or "semver") pattern is often used. This versioning mechanism allows downstream consumers to understand the impact of changes made and then create rules for which versions of the upstream project they will allow in their downstream systems. The semver pattern generally states that there are three parts to the version number: major, minor, and patch. This might be represented as 2.12.3 for some example project.

When the maintainers decide it is time for a release, they can bump up either the patch, minor, or major number indicating minor fixes, new features or functionality, or serious breaking changes, respectively. For example, a small bug fix that does not change the interface might indicate the new version is 2.12.4, but a new feature (that does not break pre-existing features) would warrant a minor update to 2.13.0, and a serious change to the interface would like result in 3.0.0 being the release. A downstream consumer can then decide if they want to accept any of these new releases.

I will remind readers that the use of semver - and adherence to the major, minor, and patch pattern - is completely voluntary and not implemented consistently in any way.

Vetting of Contributors

The open source community is a meritocracy.

(Yes, yes we can argue and debate over how true this may actually be. Nothing is ever perfect, but generally, this statement holds true for much of the open source community.)

That is to say, if you write good code that solves a problem and abides by the contribution guidelines, your submission will generally be accepted. This elevates you from random community member (and consumer) to code contributor (producer), but does not necessarily grant you any control over the underlying code repository such as changing security settings or reviewing other inbound contributions.

Most core teams for popular open source repositories have guidelines on who can be added as a core team member. These guidelines are often not published, but rather some internal understanding or agreement among current members. This means that those guidelines can change over time as core team members change. That said, in most cases permissions are gradually increased, giving the user very limited access at first.

More established open source projects such as OpenSSL or Debian Linux have well established - and often arduous - criteria, but they are still predominately meritocracies. Corporate sponsored open source projects such as Facebook's React UI framework are company-controlled, and while they might have some core contributors from the community with heightened access, the highest privileges ("owner" access) are restricted to company personnel.

The most important fact here is that aspects such as the employment, personal life, country of origin, political affiliation, or other non-merit-based aspects of a contributor are typically not sought out and not considered when someone is given access to a code repository. In fact, true "in real life" identity is sometimes not known at all for core members of large open source projects.

Open Source Licenses

Warning: I am not a lawyer. You should seek legal counsel for any real decisions on intellectual property.

In general, intellectual property falls into one of four types: copyright, trademark, patent, and trade secrets. We're mostly going to focus on the first (copyright) as it is the collection of rights that an open source license generally releases to the public. An open source license is a legal agreement between the producer and consumer, by which the producer sets the rights and responsibilities conveyed to the consumer by using their software. Notably, trademark and patent issues are also a concern in open source software, but I will not be covering those in this article.

First off, posting code publicly does not necessarily mean others can use it, and that alone does not meet the definition of "open source." This is a common misconception. In the United States (and a number of other countries), as soon as a work is created (for example, the code is written) a copyright is created and possessed by the author. In order to protect that copyright the author might need to file for a certificate with the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), but the copyright exists regardless, and could be enforced later.

In common use, we (the developer community) don't generally consider something to be "open source" unless an open source license is attached in some way. For example, there could be a text file in the root directory of the code repository called "LICENSE" which has the text of a common open source license in it. Often times the manifest file (there's an example of this later) also specifies a license by name (for example, "MIT" or "GPLv3").

If no license is specified within the code repository, the website for the code, or some other related document or artifact, then the code is likely not open source software (even if the source code is published online). It's also important to note that the copyright is independent of the license. Attaching an open source license to a code repository does not change who holds the copyright.

Of critical importance here is that an author (the copyright holder) can change the license any time they choose. And that could be to make it more restrictive or more open! This famously happened - and then was changed back - by the immensely popular React UI framework owned and published by Facebook.

Choosing an Open Source License

Developers are able to choose any license they wish, or none (thus retaining all rights). Every license falls somewhere on a spectrum from highly permissive to very restrictive. The "MIT" license referenced above is very permissive because it releases nearly every right a consumer could want. Of course, it comes with absolutely no warranty and is provided 100% as-is with no expectation of support of any kind. You can view many licenses in a categorized fashion on the OSI website.

In many cases an open source developer will choose a very permissive license when they start their open source journey. They might then pull back to a less permissive license later, but that often does not happen. An important thing to remember is that open source developers are just that: developers. They are (usually) not lawyers and have no background in intellectual property rights and protections. Often times this means the developer will simply choose a license they see on a popular code repository they use, replicating it without thinking.

If a developer does take time to think about the license they use, there are a few questions they might ask themselves:

- Do I care about patent rights on any of this work?

- Do I care about requiring improvements to my software to also be open source?

- Do I care about the license used on derivative works?

- Do I care about compatibility within another project or platform?

This is another reminder that I am not a lawyer and you should consult with one if you have questions on open source licenses. That said, here's an interesting set of data on the most popular licenses (by pageview and visitors) to the relevant OSI webpages in 2024, with the MIT, BSD-3, and Apache 2.0 licenses accounting for around 77% of all traffic.

Open Source Consumers

As you may have already read above, producers are almost always consumers as well. Most open source repositories try to not repeat the work of others by incorporating smaller chunks of functionality from existing open source modules. This truism is not reciprocal - there are many consumers that have no role in the producer journey. This fact is actually one of the biggest issues in the open source ecosystem: the imbalance of consumers to producers.

The primary motivation of a consumer is reuse. The ability reuse software written by another is extremely valuable. Of course, their selection of an open source project to include in their own should include a review of their intended use. If you recall the license conversation immediately above, the way an open source project is allowed to be used may be dictated by the license. However, often such considerations are an after thought.

A consumer of OSS will typically find available upstream projects by simply searching online. Results could come from many places including hosting platforms like GitHub and GitLab, question and answer sites like StackOverflow or Reddit, or from their language's package manager (like npm for JavaScript or PyPi for Python). Once the developer finds a solution to the particular problem they were trying to solve within their own project, they will typically not seek a different solution unless there is very good reason to do so. In other words, it is rare for a consumer to switch from a chosen OSS dependency to a new one, even if the original has a severe security flaw.

This lack of change isn't necessarily a conscious one: often a downstream developer simply does not know that one of their upstream dependencies has a critical vulnerability. However, this lack of security awareness is in fact a massive problem in the ecosystem! It allows insecure projects to continue to be used well after they should be retired.

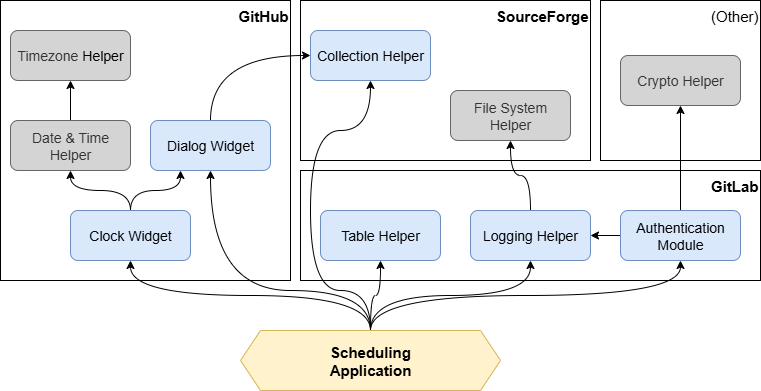

Notional Application Dependency Tree

Let's look at a possible supply chain that ends in a finished product (a notional "Scheduling Application" at the bottom of the diagram below):

In the diagram above you can see that our application uses a number of other modules as dependencies, which in turn use other modules as their own dependencies. These dependencies can be hosted on multiple different platforms, and often times a single module can be a dependency of many other modules. In this manner, we can easily see how a vulnerability or bug in the Collection Helper codebase in the diagram can have a wide-reaching effect.

How are dependencies specified?

In most programming languages there are one or more "manifest" formats that allow software engineers to specify what dependencies they require and then a "manager" that can use the manifest to retrieve the upstream dependencies. One example is the "Node Package Manager" (npm) in the Node.js platform (based on the JavaScript programming language). The npm tool provides a command-line interface (CLI) for an engineer to both specify and download a dependency, regardless of where it is hosted.

Below is a command to install a dependency (the imaginary "collection helper" referenced in the diagram above) and to automatically add the latest version to the project's manifest (the --save option):

npm install --save clock-widgetBy issuing the command above the developer is simultaneously downloading the dependent software and adding it to a manifest which includes the name and version of the software installed. This manifest is used by all developers on the project so that they can all install the same version of the dependent software. (Technically, the symbols you see below could allow two developers to have different upstream dependency versions, but many languages have a solution for that called a "lock file," but that topic is for another time.)

Here is what an npm manifest might look like:

{

"name": "scheduling-application",

"version": "1.1.0",

...

"dependencies": {

"clock-widget": "^1.0.2",

"collection-helper": "^1.0.2",

"dialog-widget": "^3.12.1",

"table-helper": "2.0.0",

"logging-helper": "^0.8.3",

"authentication-module": "^12.4.23"

}

}Other programming languages and frameworks have similar commands and manifests, but in various different formats, making interoperability and cross-language tracking very difficult. Complicating the matter even further is that in some cases no manifest is used at all and the dependent software is simply included in the primary application's own codebase.

Note above how the "semver" format is used to track both the version of this "scheduling-application" and each dependency. The ^ symbol you see above will allow npm to install more recent versions of those dependencies, for example, installing "clock-widget" version 1.1.0 once it is released, even without the need to update the manifest itself. This is the reason developers often use a "lock file" to nail down ("lock") specific versions of upstream libraries.

Finally, note that this list does not include 100% of the upstream software we need, because it does not include the indirect or transitive dependencies: those installed because they are needed by the direct dependencies. They're still part of our Scheduling Application!

Choosing the Upstream Dependencies

Unfortunately, the criteria for choosing an OSS project to solve a small problem within a final system is extremely varied, even within the same team. When choosing a foundational dependency like the broad framework for a web application or the programming language to use the choice is often very thoughtful, typically with lots of criteria. For example, choosing to use Drupal versus Wordpress for a content management system. However, when choosing which OSS module to use for handling date and time information the choice is largely just "did the dependency solve the problem"? And less around interoperability, documentation, testing, security, etc. Additionally, these choices are often made by single developers and not through a rigorous vetting process.

Broadly speaking, there are five big criteria that tend to be used when making the big choices in OSS (like a big web framework). These criteria are presented below in an ordered list as they are often approached by a developer or team, with the caveat that different organizations will obviously structure their decision making differently.

1. Functionality

Answering the question: does this piece of open source code do what I need done? But this criteria also extends to: can I configure it to solve my problem in other ways?

2. Popularity

The number of "stars" on GitHub or download counts can often be a proxy for the support that this code library has within the community. Two modules equal in functionality but one with 500 stars and one with 10 stars typically makes for an easy decision. Of course, these metrics are often paired with other criteria like velocity.

3. Documentation

How easy is it for a developer to know how to use this code library? If a developer spends more than an hour trying to figure out how to solve their problem they are likely to move on to a different library. Aside from functional documentation, an experienced software engineer will also be looking for strong contribution guidelines, build and test metrics, security protocols, etc. Lastly, this category also applies to the OSS license used; however, it is exceedingly rare that a developer will choose one library over another based on the license. This is more likely to come up in a review by organization lawyers or compliance officials, forcing a change.

4. Velocity

When was the last release of this code? How often are contributions accepted and how quickly are issues addressed and resolved? Related to this category is the number of contributors on the repository. If it is a single developer maintaining it, there will be some concerns. More contributors means higher velocity, but it also means more eyes on problems and thus generally better solutions.

5. Testing & Security

Often testing and security are after thoughts in the decision making process. A good senior developer will be looking for this, but often the first three criteria above are enough to make the decision of whether to use an open source module. In almost all cases, large organizational reviews don't even catch this criteria outside of known, reported common vulnerabilities and exploits (CVEs).

Risks to Consumers

If an open source consumer does their due diligence and selects only good, well maintained, well tested, and secure open source dependencies following the guidance above, then where is the risk?

Deep Dependency Trees

Refer back to our notional application dependency tree from earlier. While the developers of the downstream project (our "Scheduling Application") might make good decisions about which dependencies to include directly, their code is ultimately at the mercy of every other - and developer - upstream. If we look at a very simple application dependency tree with six direct dependencies (like our notional application) we could easily be dependent on dozens or even hundreds of sub-dependencies, and thus hundreds or thousands of other developers.

There are tools to get insight into this deep dependency tree, but at some point we accept some amount of risk when building software this way. All of the other risks in using open source software are amplified by this one aspect. A downstream project can partially mitigate this risk by ensuring that they have automated processes in place to review their full dependency tree for issues not just on new builds, but continuously.

Lack of Participation

While there are multiple benefits to using open source software, the one that gets the most attention tends to be the "free" nature of it. The word "free" here is in quotes, because we all know that nothing is ever truly free. It is true that most OSS is, in fact, FOSS ("Free and Open Source Software"); however, that doesn't mean that it will be free of all costs to the downstream consumer.

When you purchase a piece of software from a vendor you are not paying solely for a license to use it, but also for all of the work that goes into making it and maintaining it. Consider Microsoft Office, a ubiquitous piece of software for most organizations. A "Personal" license for the desktop software costs about $100 in 2025. But the consumer will receive updates to that software over time. The cost is also spread among many users, and thus the developer (Microsoft in this case) is able to fund quality, secure software development processes. (Let's ignore for the moment the fact that Microsoft doesn't have the best track record for producing secure software.)

Now consider a critical piece of open source software. In nearly every case it is being built and maintained by unpaid volunteers. A downstream consuming organization does not need to pay money, but they also are not entitled to any bug or security fixes, any feature updates, or any support in any way from the upstream maintainers.

So what happens when you do find a bug in a piece of open source software? Most people will wait, expecting the volunteers to fix the issue. And therein lies the problem: the cost of open source is hidden behind a lack of participation.

In order to better trust open source products, we as a community must participate in their development and maintenance. Organizations will either put in the cost on the front end through participation in the development process, or they will put in the cost on the back end when things are buggy, broken, insecure, or no longer supported by the volunteers.

Single Points of Failure

Building up on the last point, open source projects are highly susceptible to single points of failure. For example, a project with a single contributor may stop being supported for any number of reasons (including both tragic and normal reasons) affecting everyone downstream. Increasing participation by organizations can alleviate this problem, but it must be consistent support and all encompassing. Submitting one code pull request is not sufficient to alleviate the single point of failure because there still may only be a single person capable of publishing a new release.

However, the "single point of failure" issue is not just about the contributors, it also manifests in some upstream dependencies that many, many code projects rely on. When one of these critical - and often small - projects faulters, the entire system can get thrown into chaos. This was put on display in 2016 when an 11-line code library was abruptly unpublished resulting in thousands of downstream projects failing to build properly.

The best mitigation for this risk is to either change to a better supported library, or possibly to create a fork and maintain it. There are cases where an otherwise unsupported piece of code has been forked and then that fork becomes the primary library in use for that purpose.

Lax Software Development Processes

For older, larger open source projects, especially those maintained by larger companies, there is usually a fairly standard software development lifecycle that includes the processes many companies would follow for their own code. This could include automated testing, scanning of code for quality and security issues, and a thorough code review step.

However, for smaller projects, and especially for those with a small number of maintainers and contributors, the software development process can be very lax. Often times testing and security is a distant afterthought to features. These lax practices then breed bugs and vulnerabilities that can affect downstream consumers.

It's also worth mentioning that downstream consumers do not necessarily have good development practices either. Thus hiding potential issues with upstream dependencies that might have security vulnerabilities going unchecked.

The solution here is better overall software development practices at all points in the supply chain, but also increased participation in open source projects by the broader community. If a company's product relies on a particular open source project, that company should get involved to espouse good development processes and thus better secure their own code.

License and Copyright Issues

One last issue that mostly affects for-profit organizations is conflicts in licenses and potential copyright issues. As discussed in the Open Source Licenses section above, there can be issues with using certain open source libraries if an organization modifies that code. This comes into play for restrictive licenses such as the LGPL (among others).

In nearly every case, a downstream consumer is required to keep the license and copyright information in tact when redistributing their own code. With some development processes it's possible that the licenses and copyrights can get stripped from a code dependency during the build process. This can open up organizations to legal issues.

Generally speaking, if an organization does not alter an open source library and maintains the license and copyright information when redistributing they should be fine, but this harkens back to the question of good software development practices above. Adding to the issue is the fact that OSS maintainers can change the license their code is released under any time they wish. The best approach to address this issue is to keep up with the projects you rely on and possibly to scan dependencies for potential conflicting licenses.

Following a Fix Downstream

Refer back to our notional application dependency tree and you will likely identify one issue with the open source software supply chain: the deepness of the dependency tree impairs a downstream consumer (like our application) to remediate upstream issues quickly.

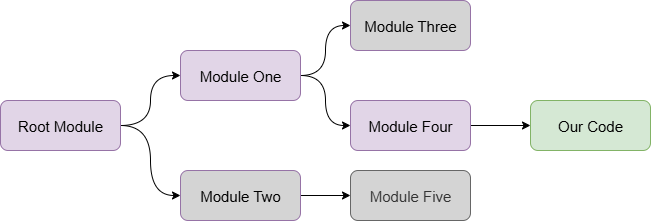

Let's take a look at one possible flow for a bug fix in an upstream project. In the explanation and diagram below, assume that the "Root Module" is a piece of open source software that not only do we not control, but is not actually a direct dependency of our software application. In this case, how will we ensure our own application is stable and secure?

1. Identification & Documentation

I see the issue in my code, but where in the dependency chain is the root of the issue?

The first step is to identify where the root cause of the issue is. Often times a developer downstream might submit a bug report to a direct dependency (in the diagram below, "Module Four"), but the core maintainers of that module might pass that issue up their dependency chain. This results in delays fixing the root cause.

2. Remediation

What code needs to change to fix the issue?

Now that we've isolated the root cause of the bug in the "Root Module", it needs to be fixed. However, if you refer to the section on Maintenance Models from earlier you might see an issue: the prioritization of this particular bug is solely up to the core team of that root module. An outside contributor (maybe even our own software developers) could come up with a fix, but it's still up to that core team to review and merge the fix.

3. Publication

Is a new version of the dependency available?

Even if there is a fix merged into the Root Module source code, there may not yet be a new release. Depending on the release process and schedule of that project there may not be a fix for days, weeks, or even months. This new release would need to be published in whatever package manager or platform that project is using.

4. Downstream Dependency Updates

Are my direct dependencies updated and new versions published?

With the Root Module updated, Module One and Module Four (see diagram below) need to both update their dependency manifest and publish their own new versions to their chosen package managers or platforms. Critically, this must occur in order, otherwise the broken code might still be in our software application as a "pinned" version of the previously buggy dependency.

5. Rebuilding & Deployment

Is our code updated, verified, and ready to deploy?

Now that all of the dependency tree has been updated, we can update our own dependency manifest to the new version of Module Four and then rebuild our code, test it thoroughly (specifically for the previously known issue) and redeploy our new version.

This process is common to nearly every programming language and software platform. There are some workarounds and shortcuts when critically necessary, but this is why it can take so long to fix a seemingly simple issue.

The workarounds tend to include things like including the "Root Module" as a direct dependency in our own code so that we are not waiting on Module One (and any others in that chain) once Step 3 is complete. However, this will not always work as some software ecosystems allow for multiple versions of the same code library to be included, thus resulting in the buggy code still existing in our application.

So why use open source dependencies at all?

Given all of the issues in the ecosystem discussed above, why do so many organizations rely so heavily on open source software in their final applications? Most of this comes down to reuse and the many benefits it brings.

Total Cost of Ownership

Even though there are many hidden costs of using open source software - and things organizations should spend money on, supporting the open source software they rely on - the total cost of ownership (TCO) for commercial software is immensely lower when all things are considered. The simple fact that the programming languages we all rely on are open source should be proof enough of that. There are some academic articles and papers that suggest that open source can lower the TCO of a software project by 80%. Additionally, consider the number stated at the top of this article about the value of open source software. If a company had to write everything from scratch, they would spend many times more than the actually value-add piece they develop.

Time to Market

This is likely the easiest - and most obvious - win for open source software. If someone else has already built it, why spend time doing the work again? While this is immensely important in the technology startup community, it applies just as much to larger organizations trying to stay ahead of the game. That said, organizations must keep in mind that incorporating open source software in their final products does require effort. Time - and money - should be allotted for evaluation of, selection for, and contribution upstream to open source dependencies.

Hive Mind Problem Solving

The time to market benefit exists not only because someone has already built a similar mouse trap and open sourced it, but because they have likely built a better mouse trap. The "hive mind" or "group thought" aspect of open source software means that downstream consumers can benefit from having many other developers looking at - and improving - the technology they would otherwise have to build in house. This almost always results in better software that can solve a range of problems versus singular use case development.

Security

While we discussed many risks in the sections above, even with such risks, the security of open source software can still be better than some closed source alternatives. Consider the "hive mind" benefit mentioned directly above: having more people looking at a problem makes the solution better. In this case, the problem is potential vulnerabilities. With more people looking at them, more people can offer solutions and fix those issues before they get exploited. David Wheeler has a fantastic chapter on the security of open source software in his open sourced book: "Secure Programming HOWTO" (chapter 2.4, specifically). One of the most compelling arguments is that closing software source code does not halt attacks. And on the contrary, closing source code can likely hide a vulnerability from your own organization, thus leaving the door open for attackers.

A Call to Action

I've raised a number of issues in this article, but I also have thoughts on how we as a community can better support our open source ecosystem. While these ideas are not necessarily new, I believe that adding more voices to the call can help.

Broader Understanding

One of the reasons I've written this article - and why I speak at conferences on the topic - is to raise awareness and understanding of the core issues facing the open source ecosystem. As I stated at the beginning of this (very long) blog post, I have had to explain the nuances, players, motivations, and critical issues of open source to organizational leaders over and over.

Hopefully, with a better understanding of the issues, leaders in our industry will step up to support the open source software we all rely on.

Adoption of OSPO's

An Open Source Program Office (OSPO) is a great way for organizations to ensure that they are being good members of the open source community and good stewards of their own open source projects. Generally these offices are only found at larger organizations as they require personnel to staff them; however, I believe that even small organizations can start with a single-person OSPO and make great improvement in their approach to both consuming and producing open source software.

Any startup that wants to make the leap to the next stage in their company's evolution should consider investing in how they think about open source software, and this is the best starting point.

Corporate Support

While an OSPO is a great place for a company to start, they can - and should - do more. While this list is not exhaustive, these are some of the more impactful and, in my opinion, easier to implement items.

- Company employees should be allowed to contribute upstream changes to open source software the company relies on - and do so on company time. Far too often a company approves an employee to work on an open source project, but then forces them to do so on personal time.

- Companies should sponsor, where possible, the financial needs of open source projects critical to their success. While some open source projects already have corporate or foundation support as discussed earlier, there are thousands of projects that do not and which could benefit from funds to pay for simple things like DevOps infrastructure, cloud hosting costs, or even a domain name.

- Companies should adopt standard processes when publishing their own open source projects to create an ecosystem where it is easier to determine cross-platform dependencies, easier to discover vulnerabilities, and easier to consume upstream software. Having an OSPO is a great way to discover and define these processes.

Government Support

As a former U.S. government employee at both the state and federal level, I have seen first hand how reliant the software that runs critical infrastructure is on the open source ecosystem. Our governments can do so much more to support the ecosystem, and unsurprisingly, it looks a lot like the corporate support discussed above.

That said, there are a number of ways that governments - especially the U.S. government - can do better:

- Establish a centralized OSPO, and with "branches" within key agencies, which establish guidelines for safe and secure consumption and publication of open source projects.

- Financially support key open source projects with grant funding. A great example of this is Germany's Sovereign Tech Fund.

- Require government IT project contractors to contribute any bug or security fixes to open source projects upstream.

- For the U.S., use Other Direct Costs (ODC's) in IT contracts to require contractors to spend time supporting open source projects the government relies on as part of their standard development practice. This is in addition to contractually requiring bug and security fixes to be pushed upstream.

I hope that this article has helped you to better understand the open source ecosystem, and more over, I hope it helps organizations of all sizes to do better in supporting this critical infrastructure that underpins our entire modern digital world. I encourage you to take this material and share it with your organization's leadership, and use it to influence their decisions on open source.

A big thank you to Tim Pepper for his review and edits!

Published on