Object Oriented JavaScript (Part the First)

Published on

Introduction

Object oriented programming (OOP) is a concept eminently familiar to those of us that have coded in Java, C++, .NET, and other languages. So why the focus on OOP? One of our primary tasks as application developers is to model the real world through code. Consider the often used example of the "Employee" and "Manager" users in a system, object oriented programming allows us to represent these two real world entities by collections of code having data and actions associated with them. In fact, that's pretty close to the definition of OOP: a way of representing things as collections of code with data and actions, including mechanisms for reusing code among related collections.

In this two part series we're going to walk developers through the ins and outs of another object oriented language: JavaScript. We'll start by talking about what it means for a language to be "object oriented", and then we'll move on to how JavaScript implements the core principles of this paradigm. JavaScript's prototype object is central to this discussion, and we'll cover the nitty gritty of what it is and how it works. In part two we'll cover prototypical inheritance, polymorphism, and the future of OOP in ECMAScript 6.

I thought JavaScript was a functional language...

Before we get into object oriented programming, perhaps we should talk about JavaScript functions and what they are. People often assume that based on how it is regularly used, that JavaScript is a functional language. To determine the basis for this we have to first understand what functional programming is. Strictly speaking, in order for a language to be "functional", any domain problem must be solvable by combining a series of mathematical functions. Each of those functions should always return the same output given the same input.

Below are examples of functional and non-functional methods:

// Functional!

function sum(x, y) {

return x + y; // given the same input, the output will always be the same

}

// Not so much here...

var x = 1;

function addTo(y) {

return x + y; // the output here will change based on input AND external state.

}We can easily see the core difference, but there are many more aspects to functional programming. The problem is that the vast majority of JavaScript code we write is done for web applications where we have to deal with a global state (the window and document objects, for example). Because of this we rarely have the opportunity to write truly functional code. That said, JavaScript can be written in a functional manner. So what are we to assume about the language paradigm? I conclude that JavaScript is a multi-paradigm language: applications can be written in many forms.

Okay, but JavaScript is still just a collection of functions...

Much of the code we write today appears to be just a collection of functions, but the fact is that JavaScript code in web applications would be more aptly described as a collection of objects. Every JavaScript function is, in fact, an object! Functions in JavaScript merely have the ability to be executed, but they are objects as well, with properties and methods attached to them:

function foo() {

return "bar";

}

console.log( foo.name ); // "foo"

console.log( foo.toString() ); // "function foo() { return \"bar\"; }"In the example above we see that our foo function actually has a name property and a toString method! You can alternatively create function objects using standard OOP syntax:

var foo = new Function(" return 'bar'; ");

console.log( foo() ); // "bar"Core Object Oriented Principles

Before we talk about OOP in JavaScript we should clarify what we mean by "object oriented." There are generally four accepted core concepts to OOP without which a language may struggle to really deem itself as such. These are:

- Abstraction,

- Encapsulation,

- Inheritance, and

- Polymorphism

Abstraction is probably the most nebulous of topics to explain, but a quote from Douglas Hofstatder is a good start:

"Abstraction is the stripping away of details so that you can see the essence."

Essentially what he is saying is that we must remove the particulars of being a specific employee and see the essence of what any "Employee" may be. For example, a specific employee might have the name "Oscar", but not every employee. Instead, each employee has a name, but not a specific value. This abstraction is core to truly being object oriented.

Encapsulation builds off of abstraction in order to form the "collections of code" that we talked about earlier. We encapsulate the properties of that employee to a single thing and additionally we encapsulate specific actions to methods (functions). For example, an employee has the ability to get a raise, but how that is accomplished is up to the implementation. Encapsulating that work to a named method on the object is essential for OOP. Some developers also attribute "hiding" of the implementation as part of encapsulation. It is not a requirement. While many languages do achieve this, it is the defined application programing interface (API) of the object that is important, not the hiding of the implementation of that API.

Inheritance may be the easiest of the four concepts to define, it simply means that one object can be described as a type of another object using the programming language's native syntax. In other words, if you describe "Manager" as a type "Employee" using the core syntax, then you have accomplished some form of inheritance. The importance of inheritance, however, is more in code reuse.

Polymorphism, our last core concept, can be translated from Latin to mean "many forms." This translation describes the concept well: the ability to have members of an object redefined at a lower level with the same name, but different implementation (form). In our previous example, having a getBonus method on each Employee could be overridden for Manager objects such that they get a bigger bonus. Having a consistent API, but different implementations for the same-named method is the essence of "polymorphism."

Object Creation

Creating an object in JavaScript is simple, you see this all around web applications using the curly brace syntax. These are typically referred to as "object literals" because they are both the instantiation and "filling" of object data in one action. In other words, what you see in the source is "literally" what the object will be:

var literalDog = { // declaration AND instantiation

name: "Vincent", // object property

speak: function() { // object method

return this.name + " says woof";

}

};

literalDog.speak(); // "Vincent says woof"A side note on

this

Inside of the

speakmethod thethisvariable will refer to the current context of the function execution. This is an important distinction with classically object oriented languages: the value ofthiscan (and often does) change! In most cases,thisinside of a method like the one above will refer to the current object or instance. Without some other influence, if a method is called with "dot" syntax as in the last line above, then you can generally expectthisinside the function to be whatever is on the left side of the dot. Inside ofliteralDog.speak()thethisvariable will refer to the object left of the dot:literalDog.

Constructors

The problem with literal objects like the one above is that we don't get much code reuse. Creating each "instance" of a "Dog" requires creating a new object literal with all data and methods. While we can pull out the methods to a single declaration, we still can't get code reuse among "child" types (like a specific "BlackLab" type). Instead of using literals, we can use a constructor function to generate our "Dog" objects:

function Dog(name) {

if (name) { this.name = name; }

this.speak = function() {

return this.name + " says woof";

}

}

var v = new Dog("Vincent");As you can see in the code above, we simply create a function named "Dog", add data and methods to the current instance (this), and then call our constructor with the new keyword. There are a number of things to note about this code. First of all, the use of the capitol "D" in Dog is only done by convention, this is not a requirement of the language. In fact, if we look closely at this code, we can see that the constructor function is really no different from any other function in JavaScript. That's an important observation: any function in JavaScript can be used as a "constructor", but of course, with we would not want to use most of them in this way.

Next, notice that we are still recreating the speak method on each instance. The function itself is declared inside of the constructor, thus each time we create a new Dog it will have its own speak method. We'll fix that a little later.

The new Keyword and prototype Object

If Dog is just a regular function, why don't we just call it normally? Why do we need to use the new keyword? To answer that, we have to understand that every function in JavaScript has a concept of a prototype; which is, generally speaking, a representation of what the newly created instance should be. Consider it an exemplar of what each and every Dog should start as. In our case, the prototype currently looks like this:

> console.log(Dog.prorotype);

{

constructor: Dog(name) {

this.name = name;

this.speak = function() {

return this.name+" says woof";

}

},

__proto__: Object { ... }

}We'll talk about the __proto__ property later, but to start, notice that in our prototype (our exemplar of a Dog) we only have one member: the constructor method. In other words, what it means to be a Dog in our system is to be created by this function. (We'll talk about default data and methods later.) When we call the Dog function with the new keyword we are asking JavaScript to do three things:

- Create an empty object;

- set the new object's prototype to point to the

Dog.prototype; - and call the

constructormethod on the new object.

The reason for illustrating what the new keyword is doing is to highlight that it is not the same as classically inherited languages. In JavaScript, new is syntactic sugar and nothing else. In fact, you can perform these three actions independent of the new keyword:

var v = Object.create(Dog.prototype);

v.constructor("Vincent");

v.speak(); // "Vincent says woof"The first line above creates an empty object and sets its prototype to equal the first argument, in this case Dog.prototype. The second line simply executes the constructor method on the object, which now points to the Dog function. You can see how constructor points to the Dog function in the previous code sample where we print out the Dog.prototype value. While using the new keyword is common practice, it is important to understand that it is only syntactic sugar. We do not need to use it in order to use and understand the prototype object or prototypical inheritance in JavaScript.

A side note on

new

There are some people in the JavaScript community who feel that syntactic sugar like the

newkeyword does more harm than good and choose not to use it at all. However, with ECMAScript 6 (ES6) pushing for more syntactic sugar surrounding OOP, it is unlikely that it will lose favor on a wider scale.

Making a Better Dog

Remember how the name property and speak method were not on the Dog.prototype object? If we are calling the prototype an exemplar of what it means to be a "Dog", then we probably want some common functionality to always be there. This will also become vital when we discuss prototypical inheritance. To do this, we simply add members to the prototype object directly:

function Dog(name) {

if (name) { this.name = name; }

}

Dog.prototype.name = "Bubbles";

Dog.prototype.speak = function() {

return this.name + " says woof";

};

var b = new Dog();

b.speak(); // "Bubbles says woof"Notice that we pulled some code out of the constructor function and instead simply added properties and methods to the prototype directly. The value "Bubbles" on the name will now serve as a default value. We can see this on the last two lines of the code above where we create a new Dog but do not provide a name. Because of this, the name property for the instance will fall back to whatever value is on the prototype. We're going to talk about this "fall back" mechanism more later.

Here is what our new Dog.prototype object looks like. This shouldn't come as a surprise since we just added code to the prototype object. There is no magic here, the prototype is simply another JavaScript object. It just happens to be used by the OOP syntax in JavaScript as a reference for how to create new instances.

> console.log(Dog.prototype);

{

constructor: Dog(name) {

if (name) { this.name = name; }

},

name: "Bubbles",

speak: function() {

return this.name + " says woof";

},

__proto__: Object { ... }

}A side note on

__proto__

You've already seen the

__proto__property in our examples. It is pronounced "dunder proto", a nomenclature borrowed from Python. Every JavaScript object will have this member and it simply points to the prototype that that object was created from. For ourDoginstances it will point toDog.prototype. Since theprototypeitself is simply an object, it also has a__proto__member, and as you can see in our examples, that currently points to the rootObjectprototype. We'll see this again when we discuss prototypical inheritance.

Member Access Types

Developers coming from class-based object oriented languages such as PHP (or Java or C++) have become familiar with three different levels of access for members of a class: public, protected, and private. JavaScript is not class-based, and as such, it doesn't have such terms exactly. Since all objects and instances are simple objects created by - and within - functions, their members instead have a specific scope. That scope is what determines the access by calling code.

That said, we can generally regard JavaScript as having two object member access types: public and private. However, our "private" variables are really just locally scoped variables which require a "privileged" method to access them. This requires some knowledge of closures, which we'll discuss in a bit.

Public Members

To equate the OOP concepts in JavaScript to a developer familiar with a class-based system let's first look at public members. Any code creating a new object instance will have access to that object's public properties and methods. This comprises the majority of the object in most cases. In fact, any member of the object that resides on the prototype, or on the instance variable itself, is public.

function Dog(name, fur) {

if (name) { this.name = name; } // public

this.furColor = fur; // public

}

Dog.prototype.name = "Bubbles"; // public

Dog.prototype.speak = function() { // public

return this.name + " says woof";

};

var v = new Dog("Vincent", "black");

v.owner = "Jordan"; // publicWe can see here how most properties and methods of an object will be public. That includes anything placed on the prototype such as the default name and the speak method, anything placed on the instance using this as it is inside the Dog constructor function, and anything placed on an instance after creation as with the v.owner property. Any piece of code in an application that has access to the Dog instance called v above would have access to all of those properties and methods with no restrictions.

Private Variables

When we talk about private variables in JavaScript it is important to note that we are not discussing private "members" of the object per se. Instead, we are referring to variables created in a specific scope such that they are not accessible outside of that scope. Below is an example where we create a variable (using the var keyword) inside of the Dog constructor. Due to JavaScript's function scope, that variable cannot be accessed outside of the function:

function Dog(name) {

if (name) { this.name = name; }

var alive = true;

}

var v = new Dog("Vincent");

v.alive; // undefined!When we create the alive variable we do not place it on the instance variable (this), instead it is locally-scoped to the Dog function and not accessible outside of that scope. You may be asking yourself how such a variable could be useful to any code outside of the Dog constructor given this code. That is where closures and "privileged" methods come into play.

A side note on closures

In order to understand what we're calling "privileged" methods in JavaScript we need to understand closures. If you're already familiar with the concept go ahead and skip down! A closure is a function which retains a reference to all variables in scope at the time the function was created, allowing it to use those variables once the function is called later, even if the surrounding scope is no longer in use. In JavaScript, all functions are closures.

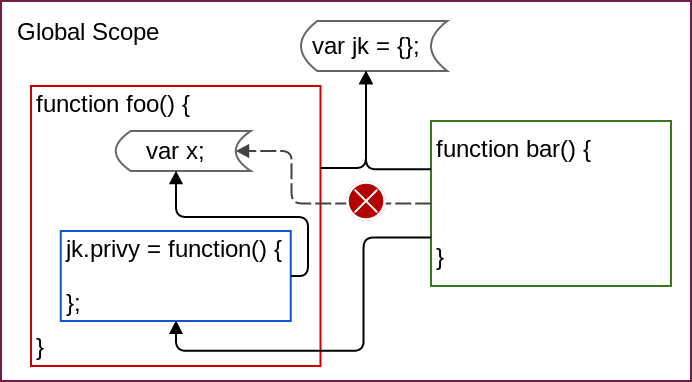

In the diagram below each of the colored boxes represent a function scope. The

jkobject variable in the "Global Scope" is accessible to all functions created within its scope (the largest box). Thefoofunction (red box) creates a new scope, and a variablexwithin it. It also creates a new function which it then places on thejk.privyvariable. Note that theprivyfunction (the blue box) is completely contained within thefoofunction's scope (red box) thus when the function is executed at a later time it will still have access tox, even if thefoofunction is no longer accessible otherwise.

The green box on the right for the

barfunction creates its own scope outside of thefoofunction's scope. This means that thebarfunction can never access thexvariable declared inside offoo(in other words,xis "private" tofoo). However, since theprivyfunction is declared on thejkobject, and thebarfunction is within the global scope thatjkis defined within,barcan call theprivyfunction. Theprivyfunction has access to variables in scope at the time it was created withinfoo(this is the definition of a closure), thusbarcan indirectly accessxby callingprivy.

Privileged Methods

In order to access the alive private variable we created earlier in the Dog constructor we will need one or more "privileged" methods. These are methods created within the same scope as that private variable and thus are able to access alive when called from outside the private scope of Dog:

function Dog(name) {

if (name) { this.name = name; }

var alive = true; // private

this.isAlive = function() { return alive; } // privileged

this.die = function() { alive = false; } // privileged

}

var v = new Dog("Vincent");

v.alive; // undefined!

v.isAlive(); // true

v.die();

v.isAlive(); // false :(Notice how the isAlive and die methods are actually created inside the constructor versus on the prototype. This is what allows them to access the private alive variable when called at the end of the example. Keep in mind that v.alive still does not exist! There is no "alive" variable on the instance, only within the Dog constructor function scope. This is how we achieve private variables in JavaScript and restrict access to them from calling code.

Static Members

We can also create "static" members for our Dog object type. These members are placed directly on the constructor function itself and give access to the static members for any code that has the ability to create instances.

Dog.genus = "Canis";

Dog.mergeBreeds = function(dogA, dogB) {

// ...

}The genus variable and mergeBreeds method are placed directly on the Dog variable (which is a function, but don't get caught up in that, remember, they're just another type of object). Any code that can access the Dog constructor could then access Dog.genus. These static members are useful for data that does not change from one instance to another and thus does not need the memory overhead of being placed on each instance separately, or even on the prototype.

A side note static methods

Be careful when using static methods, you do not have access to a specific instance inside the method! Unlike the

speakmethod, inside of a static method thethisvariable will not refer to an instance, but instead will default to whatever is on the left of the dot in our dot syntax. For example, if we had a staticDog.getName()method and tried to accessthisinside, what would we get?

Dog.getName = function() { return this.name; // What is "this" inside the method?? } Dog.getName(); // What will this return?

> Our `getName` method above will return the `name` variable of `this` inside the function body, but `this` will not point to an instance of a `Dog`. Instead, it will point to the variable to the left of the dot... In the example above that means the `Dog` function itself. And the the name of the `Dog` function is... "Dog"! And that is exactly what will be returned each time.

### Wrapping Things Up

In this first installment of our two part series on object oriented JavaScript we have learned a lot about objects and functions generally, constructors and `new` in JavaScript, and various object member types. We can begin to see how the `prototype` object is used to create new objects following a pattern, and how we might use JavaScript to model real world items. In addition we've studied how functions operate in better detail, allowing us to create private variables, access object data.

In the [next post](/object-oriented-javascript-part-the-second) we'll introduce prototypical inheritance and polymorphism and round out our object oriented structure. We'll build off of our `Dog` example and go even deeper on the `prototype` object and JavaScript's fall back mechanism. Additionally, we'll introduce you to the future of objects in ECMAScript 6 and both what to expect, and what to watch out for, in the next generation of JavaScript.

### Reference Links

* [Kyle Simpson's book on this & object prototypes from the "You Don't Know JS" series](https://github.com/getify/You-Dont-Know-JS/tree/master/this%20%26%20object%20prototypes)

* [Douglas Crockford on private variables](http://javascript.crockford.com/private.html)

* [Documentation for `Object.create()`](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Object/create)

* [Documentation for `FUnction.prototype.apply()`](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Function/apply)

* [Table of browser implementations of ES6](http://kangax.github.io/compat-table/es6/) (and [ES5](http://kangax.github.io/compat-table/es5/))

Published on